Aristotle -> Aquinas -> Atheism, Part 3

by nonewsisnew

We turn now to looking at each proof in it’s own right, and how that fits within Aristotelian causes and how that in turn effects the Christian and New Atheist (through Dawkins) understanding of the proofs.

Proof 1: The unmoved mover.

This proof of God relies upon the efficient cause. In particular, the efficient cause in relation to motion, and why anything moves.

Aristotle first shows that there is an unmoved cause of all motion. He does this by pointing out how motion is an everlasting quality, things always have the property of motion (A force vector might sum to 0, but it still has the property of being a force vector). To be in motion that is more than zero feet per second, there needs to be a something to cause that motion. As this website states: “Efficient causes, according to Aristotle, are prior conditions, entities, or events considered to have caused the thing in question.” There must then be some unmoved prior condition which effected (aka, caused) the first movement. As Aristotle states: “for in fact there is something that initiates motion without being movable” (Physics, Book 3, 201a). This cause of motion is outside the realm of moveable things because it is a prior condition to movement. In short, the argument he makes is that all moving things we know about have been acted upon by another agent. I can think of nothing now moving that wasn’t first forced into motion. As Isaac Newton’s first law of motion reminds us, resting objects will stay resting unless forced to do otherwise.

Following this, Aristotle goes on to say: “Since motion must be everlasting and must never fail, there must be some everlasting first mover, or more than one. The question whether each of the unmoved movers is everlasting is irrelevant to this argument; but it will be clear in the following way that there must be something that is itself unmoved and outside all change, either unqualified or coincidental, but initiates motion in something else.” (Physics, Book 8, 258b) Simply put, there must have been one or more than one prior conditions to achieve motion in our universe.

Aristotle then ends up with: “If, then, motion is everlasting, the first mover is also everlasting, if there is just one; and if there are many, there are many everlasting movers. But we must suppose there is one rather than many, and a finite rather than an infinite number. For in every case where the results of either assumption are the same, we should assume a finite number of causes; for among natural things what is finite and better must exist rather than its opposite if that is possible. And one mover is sufficient; it will be first and everlasting among the unmoved things, and the principles of motion for the other things” (Physics, Book 8, 259a) In this way Aristotle shows there is only one eternal unmoved mover. An eternal condition which creates movement.

Stealing the whole shebang from Aristotle, Aquinas points out that a singular eternal source of motion sounds an awful lot like how Christians describe God as creator and sustainer of life. As wikipedia translates him:

The first and more manifest way is the argument from motion. It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality. Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it. Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

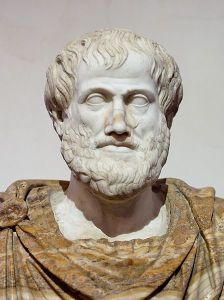

At this point it should become apparent that Aquinas isn’t in an fight to prove the existence of God, but rather to engage Aristotle in such a way as to unite Aristotle’s reason to Christian faith. Those Christians who utilize this as a proof of God shouldn’t treat this argument as though it exists in a vacuum. Only upon accepting Aristotle as correct in his secular logical argument that we need an eternal unmoved mover does this point of Aquinas hold any water. As Dawkins treats the first three proofs of Aquinas as one, I’ll hold off discussing his rebuttal of Aquinas ’till the third proof. Suffice it to say, Dawkins disagreement is that Aristotle’s eternal unmoved mover should also be subjected to motion. In his book, The God Delusion, he fails to point out any logical problems with Aristotle’s (and subsequently Aquinas’) proof, and he instead denigrates Aristotle by saying his logical proof of an unmoved mover immune from movement is merely an “unwarranted assumption” (for more, see the third chapter of his book). It’s hard to believe someone so bright as to be called “The First Teacher” could have made an oversight both as grand and as previously unnoticed as Dawkins seems to propose it is.

[…] from the last post how Dawkins considers Aristotle to be making the vaguely phrased, “unwarranted […]